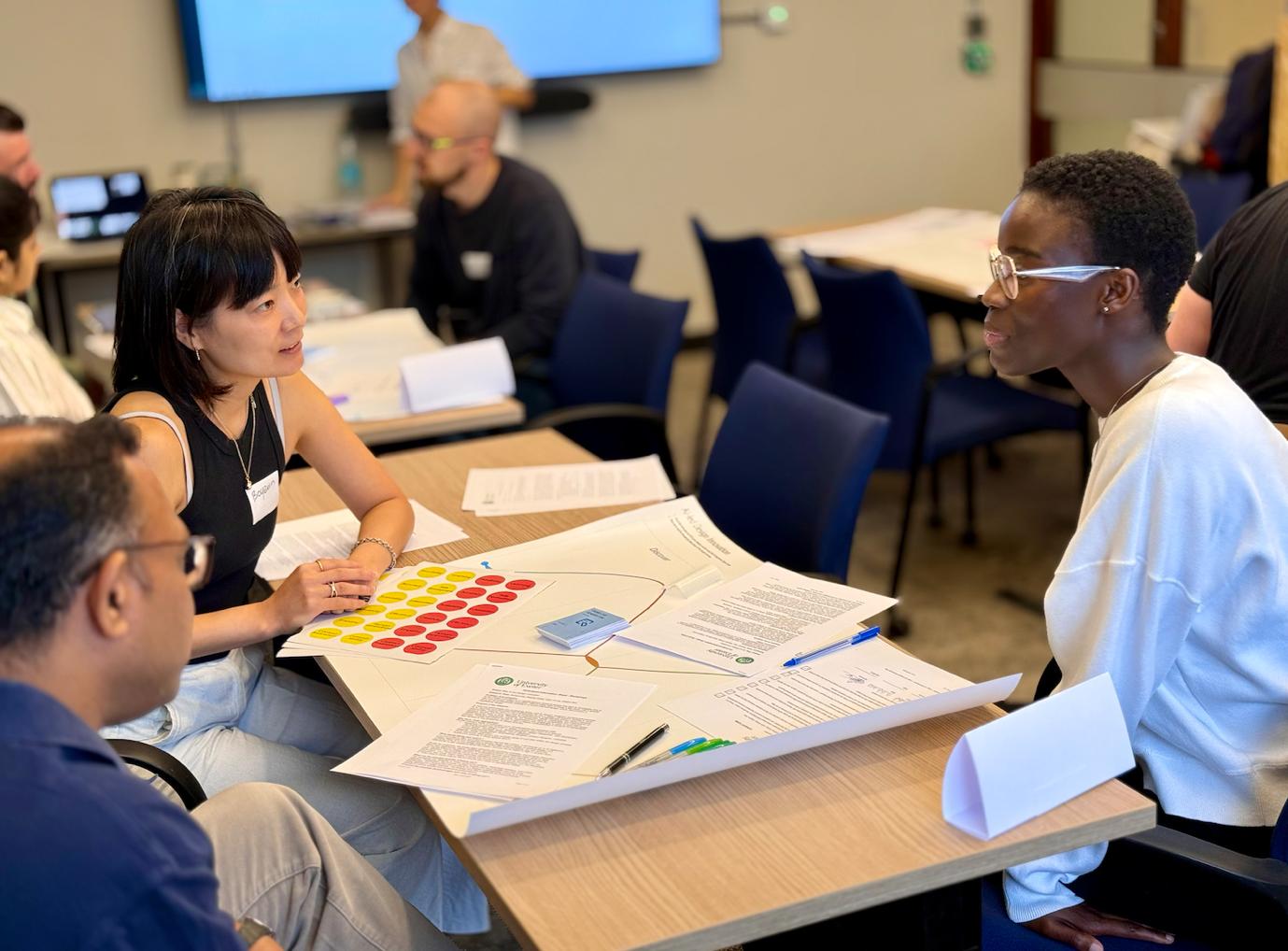

On 17th April I participated in a TechUK panel of people considering the impact COVID-19 is having on local public services, together with the themes that will be very important in shaping our Place-based post-COVID future. I was joined by Paul Brewer, Director for Digital & Resources, Adur & Worthing Councils, Helen Gerling, Managing Director, Shaping Cloud, and Ingrid Koehler, Senior Policy Researcher, LGiU – and we were chaired by Georgina Maratheftis, Head of Programme – Local Public Services, techUK. It was a very rich discussion, and I’d like to capture some of the topics that caught my attention.

Full access to this panel is available here.

Beginning the discussion, I divided my observations (based on my involvement with Methods’ Local Government team, as well as my work as an academic) into three areas: observations about how COVID-19 has affected local services to date; areas of emphasis for councils post-COVID; and some challenges for social services in delivering on these. Looking first at how COVID-19 has affected local services to date, we’ve seen a removal of much of the previous organisational policy inertia surrounding the shift to digital – the most significant shift to digital we are likely to see in our lifetime. Councils that had been resisting cashless payments, for example, have gone paperless within weeks; we have also seen a major shift towards digital service delivery, greater acceptance of data sharing, a move to the cloud, a radical shift towards home based work (Birmingham City Council alone has moved 400 contact centre staff online), and a move away from the often huge meetings that used to be the norm in so many of our councils.

In addition to this accelerated technology adoption, we have seen much more cross-boundary collaboration: for example, between NHS, police, ambulance, and 3rd sectors. Much of this collaboration has been coordinated by councils. Innovation has also accelerated. Some councils have been re purposing and scaling up technology pilots for use in new areas that they had not expected: a good example is Swindon Council’s use of process automation to improve the distribution of school meal vouchers. Digital teams have never been more important than now: in offering tools and new ways of working to enable councils to co-ordinate the broad ecosystem of place-based care that has mobilised in response to COVID. Such communitarian collaboration has sprung up at a scale that has surprised many who thought that community had been irrevocably shattered by sectarian division post-Brexit: this has undoubtedly been one of the greatest positives to emerge from our national crisis. Yet the crisis has also exposed weaknesses in local government: gaps in technology provision, data and intelligence, delivery resource, and single points of failure – as well as society’s increasing reliance on private sector infrastructure for communication and delivery (consider the growing role – and wealth – of AWS and Amazon, for example).

Turning to areas of emphasis for councils post-COVID, the shape of the new normal is likely to include more social distancing, localism, focus on supply chain resilience, and redefined sector boundaries. Having had a taste of some of the fabulous cross-sector collaboration around citizen need of the past few weeks, few will wish to revert to some of the most traditionally siloed models previously on offer. Staff, too, may naturally wish to share in the dividend of improved work-life balance that often accompanies flexible, remote work and reduced commuting. In return, the hope is that many of them will be persuaded to abandon the relative comfort of traditional professional and divisional boundaries and participate willingly in agile, collaborative working, bypassing the ‘signoff culture’ of traditional hierarchical bureaucracy and using data to spin up interventions quickly, when and where these are required.

Such interventions will use data modelling and scenario planning much more effectively to build a deeper understanding of Place (physical and online) against citizen need – and possibly use predictive analytics as well as crowdsourcing to rapidly establish, and socialise, political will and legitimacy around these. Finally, we can expect an acceleration in councils’ inevitable shift away from physical infrastructure and capital – towards ‘hub’ models that aggregate demand and commission delivery against such demand from a range of actors – part of a relentless shift that I am convinced we will see in the local government space towards multi-sided platform delivery models.

Third, as a result of the growing acceptance of digital technology and associated working patterns in our lives, councils are likely to face some particular pressures. Perhaps most importantly, they must not allow the gains in efficiency and productivity that we’ve seen during the past weeks to lapse back into the old ways. Moreover, such gains need to be parlayed into services for the most vulnerable, not cashable savings. Capabilities to adapt and respond quickly, and in agile fashion, must not be mothballed and forgotten.

In order that this happens, councils should consciously – mindfully – pause before restoring their services to business-as-usual post-COVID. My local government colleagues at Methods talk about a ‘reverse business case’: a structured way for councils to ensure that they retain the benefits of these new capabilities and new ways of working, and are working on a free web-based offering that can help councils with this thinking now. A reverse business case is a data-driven approach that considers whether mothballed services can be configured better for a post-COVID environment. Councils should complement such analysis with social listening and sentiment analysis tools to gauge how citizen priorities and expectations may have shifted during this period, so that resources are immediately pushed to the right place.

Ingrid Koehler then made a number of interesting comments around the way in which the crisis had opened up spaces for collaboration that were previously backgrounded, as well as highlighting shortcomings that many knew were there but for which post-COVID there may now be less excuse. Addressing the isolation of many older people was an example of a social issue on many peoples’ minds, but the way in which we have seen armies of volunteers surface in the Responder app (supply) who lack the ability to be connected to people who need them (demand) surfaces the realisation that digital apps are perfect brokerage solutions for connecting supply with demand in local services – especially in distributed, multi-agency, multi-sector contexts – if only we can figure out how to make proper use of them. We can surely expect demand for these to grow – along with demand for civic data trusts (as suggested by another participant): ‘data homes’ for the vulnerable and the volunteer base alike to regulate and validate local data; such trusts could also support local telecare devices with locality-based views. As Ingrid pointed out however, we must be careful to balance this new openness with accountability; perhaps civic data trusts might help.

Paul Brewer then offered a range of insights from within Adur and Worthing Councils’ digital team. He observed that it had been surprising just how much people could get done when the pressure was on: as an example, his team had built a referral function to quickly connect people in need of assistance into the voluntary sector, using Google APIs to optimise for proximity – this was done in 48 hours onto the Councils’ existing platform. For Paul, the team’s ability to deliver this sort of functionality so quickly had raised further questions about how councils can further build on this sort of approach to collectively develop a more emergent, organic and responsive understanding of ‘what a community is’ – and of course, what the proper role of the council is within this. Paul believes that we will see a renewed emphasis on civic infrastructure – data standards, electric vehicle charging points, digital platforms to enable neighbourhood teams – even the high street itself. The council will be a steward, a curator, a hub facilitating the release of value across the locality by a diverse range of actors.

Finally Helen Gerling offered a number of trends that she had observed more generally during the crisis to date. These included the move to distributed workforces, the increased capacity of home-working infrastructure, cross-organisational working, growing recognition of the importance of community groups and data, and a loosening of traditional information governance controls where danger-to-life is considered a greater risk than danger-to-privacy. Like Ingrid however, Helen pointed to the need to ensure that privacy and governance is restored properly as this relationship reverses in a post-COVID world.

There were many more interesting insights during this discussion – too many to include here. In sum, perhaps my overriding impression is that local services are a hive of urgent thinking, but also of reflection, about how councils can best add value post-COVID. There was urgent thinking – about how we can build much more firmly upon the improved connectivity we have seen emerging between councils and voluntary groups during the crisis; however there was also reflection – about the future role of councils, as data brokers, scenario planners, stewards, referrers, and commissioners within this more networked, more communitarian Place. If they get it right, councils could underpin and support us citizens as we practise our community, with all the inclusivity this implies. And that has to be a post-COVID vision worth striving for.