A range of fascinating topics

During the last few weeks, I was fortunate to be asked to speak and participate in a series of events with Leaders groups (including the Councils, Chamber of Commerce, professional organisations) in the South West discussing evidence-based practice and policy on the Future of Work is Now. Topics covered four themes (Skills, Human Aspects, AI/Technology and Business Operations) and included politics, ethics, culture, skills, teaching techniques, the changing role of universities, operations management, AI, home working, complexity, and empathy, to name a few. It’s clear that all of these are hefty topics in themselves, because they are all changing – moving beyond the boundaries of anything we have experienced as a society before, and raising concerning questions of how we prepare our young people for an uncertain and fast-changing-changing world. At points, the discussions were very humbling indeed: it was clear that we collectively have much to learn.

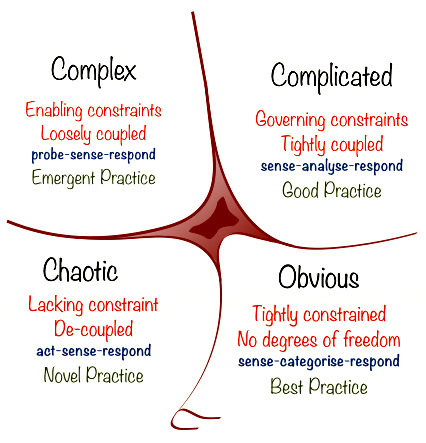

Rather than try and summarise them all, therefore, I’d like to reflect on the final two: complexity, and empathy, and how effectively approaching one can help achieve the other. Our conversation started with an acknowledgement of a growing sense of disempowerment and/or alienation felt by many who feel unable to cope with the growing complexity, and speed, of the technologically-infused world around them. I was reminded of Dave Snowden’s Cynefin model.

Dave Snowden’s Cynefin framework

Starting at bottom-right of the model, the ‘Obvious’ tends to govern linear relationships of cause-and-effect: when I turn on the kitchen tap, I can expect water to come out, with little variation on that pattern (!). In ‘Complicated’ things are a little more variable, but can still be modelled: I realise that skyscrapers are built to bend a little in the wind, but I’m confident that these variations – and structural responses – have been modelled to cope with this complexity – we understand the limit of possibilities. In ‘Complex’ however, the world is emergent: one event opens up new possibilities that people were previously unaware of – and indeed, probably didn’t exist. This is the domain of the social – interactions involving people. Finally, Chaotic is even less modellable, since events feel random.

It’s the third quadrant I’d like to focus on – the Complex – and reflect on how Snowden’s insights help us to find empathy in a digitally-complexified, fast-moving world. Rather than ‘categorisation’ or ‘analysis’, which seek to identify ‘good’ or ‘best’ practice, Snowden reflects that the appropriate approach to understanding complexity is to ‘probe’, and to understand that practice is continually emergent: although understandable in hindsight (most of the time!), it’s continually changing. In turn, this means that approaches to deal with aspects of the complexity that bedevils (empowers?!) most organisations today should feel emergent and iterative – a version of John Boyd’s ‘OODA’ – Observe-Orient-Decide-Act; they should build and maintain situational awareness, and continually reposition their value propositions against this emergently evolving background.

So how does this help us to find empathy for others – to build human-centred, ethical working environments, products, and service offerings? The answer lies in combining rigorous focus on data about people and what they want (the ‘Probe’ in Cynefin or the ‘Observe-Orient’ part of Boyd’s OODA loop), with a willingness to work in small chunks (‘Decide-Act’), continually circling back around the loop like an echolocating bat. If we add to this fundamental dynamic our increasing ability to consume digital services from others that saves us from building them all ourselves (think banking apps, white-labelled process management, AI/machine learning, optical character recognition, natural language processing, geolocation services, cloud storage, APIs to others’ service offerings, etc), we start to be able to move very fast in response to what our data tells us people actually – and emergently – want (Cynefin 3) as opposed to what more traditional methods of categorisation and analysis tells us they ought to have (Cynefin 1 & 2).

A recent example of how working in this way has enabled empathy in the midst of chaos has been UK councils’ widespread adoption of digital payments for residents during the COVID-19 lockdown, where people were understandably nervous about the various physical interactions that have characterised such payments for local services for decades. In the space of 2–3 weeks, swathes of councils recognised the problem (Observe), gathered user research about peoples’ worries in this regard (Orient), gained agreement, overturning in some cases deeply entrenched resistance to digital payments (Decide) and then enabled digital payments by calling out to third party providers (Act). The result is a piece of strikingly empathetic corporate behaviour, when compared to the Kafka-esque nature of many traditional public services.

This sort of example shows that it is indeed possible to optimise the relationship between complexity and empathy in the emerging digital world, and to help those whom we teach to understand how to bring this about for themselves. In an emergent world, pedagogical techniques based on categorisation and analysis alone, and the transmission of these as pre-baked ‘facts’, will increasingly fail; instead, we need to equip people to understand the nature of digital complexity, and offer them the techniques to shape a more empathetic world for themselves.

The ‘Future of Work’ panel discussions were organised by Ilke Incoglu, facilitated by Sawsan Khuri, and hosted by the University of Exeter. The project is supported by the LEPs Skills Advisory Panel and funded by a Policy Engagement grant from UKRI and Research England.

“The Future of Work is Now” event series was organised by Professor Ilke Inceoglu, Exeter Centre of Leadership, and Future of Work Initiative, University of Exeter Business School and facilitated by Sawsan Khuri, Collaborative Capacities. This project was supported by the LEP’s Skills Advisory Panel and funded by a Strategic Priorities Fund from UKRI and Research England.