In December 2019, shortly after the Conservative government was elected with a landslide victory, I wrote a piece in Computer Weekly exhorting our new government to make use of its precious majority to embark on an ambitious modernisation of our public services. Whilst subsequent events – some unavoidable, others politically manufactured – have undoubtedly intervened in the UK’s ability to deliver citizens the public services they expect and deserve, it is also the case that there has been little-to-no interest whatsoever in thinking about wholesale modernisation. With the UK heading into the most difficult winter for decades, our public services will be under unprecedented strain. Many are already on their knees, having been pared to the bone following years of austerity.

I have been saying this for some years now, but I believe we could all have well-funded public services, for the same money, with well-paid public servants, empowered to do things better, and more efficiently. I believe cuts, and current budget constraints, are totally unnecessary, and could be reversed.

My 26 years working as a professional adviser in the public sector (from which I have just stepped back) has shown me that unless we do something radical to modernise the way our public services are organised, they may quite literally collapse within a few more years; many are starting to collapse already.

As a business school academic, I look at other organisations for ideas. ‘Customer first’ organisations, in particular, realise they can do great new things for people by using technology to offer customers more choice, accessibility, and personalisation, often more efficiently, and thus cheaply.

Seems like a win-win – and a way of organising that we might be able to use in our own public services. So what’s the secret?

Leading ‘customer-first’ organisations tend to remain very focused, all the time, around their purpose: the reason they exist. They regularly cut away all the other distractions and agendas that creep into all organisations over time, and refocus their energy, time, and budget on that purpose, which is usually organised around some sort of customer.

Anything that doesn’t directly touch customers (in government, this means citizens on the front line) in ‘customer first’ organisations is rigorously standardised, reduced, re-used, recycled, consumed, and commoditised. Strategic focus, and budget, is constantly reoriented to the frontline – the only part that customers actually care about.

Our public services can become ‘citizen first’ public services again, refocusing rigorously on doctors, nurses, teachers, social carers, etc, and not on managerial activity & duplicated infrastructure: for me, this means more, better-paid, and intelligently-supported, public servants. A rigorous, and radical, sharing of data, service patterns, processes and systems across most of our public services could – definitely – save an absolute fortune: many billions each year, which could be redirected to hire more doctors, nurses, teachers, etc. By sharing data, they could also be supported to do a[n even] better job, as well. Quality would go up noticeably.

Given this extraordinary opportunity to have more, and better, public services, delivered by better-paid public servants, for no more money than we’re paying now, as an academic interested in this topic, I feel it my public duty to ask the following uncomfortable, and (in some quarters) unpopular questions:

“How much of the UK’s public service operational budget is spent on non-frontline services? 20%? 30%? 40%? More than 40%?”

And:

“If we were able to reduce the % of public services’ overall budget spent on non-front-line services down to a manageable 15%, how many billions could we save every year to spend on hiring more public servants, and paying them all properly? £10 billion? £20 billion? £30 billion? If we were to do all this, is it true that there would need to be absolutely no more cuts to public services at all?”

So: with [yet another] new prime minister entering Downing Street, my December 2019 challenge still stands: the sort of radical modernisation of public services I am talking about could be achieved rapidly – ie before our public services start to collapse – via legislation, and steered by a Minister for Government Transformation (sole brief), with a direct mandate from, and accountable to, the PM.

That Minister would need to have had an excellent crash course in digital business models, platform/ecosystem growth and dynamics, and at least a workable understanding of cloud-based technology. They would need to be closely supported by a small but very capable team.

They would also need a very robust character, since wholesale consolidation of back-infrastructure of public services across health, social care, housing, and local government (we could also do the same thing across universities, and police forces) will meet stiff resistance from a broad range of stakeholders with an interest in preserving the status quo, from both public and private sectors.

Importantly – and I realise this will be an unpopular message for some – none of this has anything to do with building ‘agile’, ‘digital’ citizen-centred services at the ‘front end’ of existing silos with all that baked-in chaos; it’s valuable DDAT (digital, data, and technology) work, but historically it has distracted from, and defunded, the urgent business of wholesale modernisation of our public services.

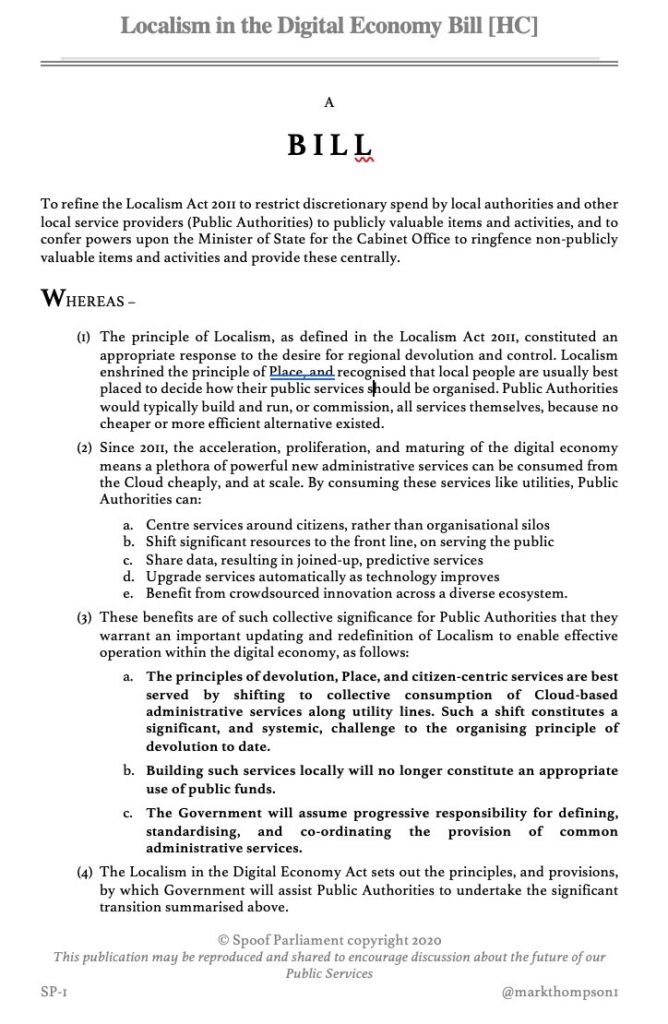

During the coming year, working as part of the EPSRC-funded DIGIT lab, a small group of us will try to ‘prove out’ the size of the opportunity that could be realised via the sort of activity shown in the draft Bill shown below. Our focus will be on radical, technology-enabled modernisation, not incremental tweaks to a broken model, because we believe UK public services may not survive another 3 years of government disinterest and inactivity on this topic. When we’re done, we’ll try to go to citizens, not the usual policymakers, because radical change is usually driven by citizens, not incumbents.

If anyone’s interested in getting involved, please get in touch with me at m.thompson6@exeter.ac.uk; we’re especially interested to hear from anyone with a background in public sector accounting and finance – for example, a CIPFA professional.