It is sometimes difficult to number revolutions. But some economists would say we’re experiencing the fifth industrial revolution: the Information and Communications version. They call earlier revolutions as:

1. Industrial

2. Railways and steam

3. Steel electricity and heavy engineering

4. Oil, cars and mass production

Each one significantly changed how society was organised: where we worked, where we lived, and how we got around.

Do revolutions mean evolution?

Revolutions tend to change who does what, and who gets what. Significant technological innovations change cost structures and communication methods. They eventually lead to new ways of doing things – a “new common sense”. These have different cost structures, and different opportunities for innovation.

And some things stay the same. During the First Industrial Revolution, new cotton mills were like scaled-up weavers “cottages”. These cottages were really home factories. Their big windows (at the top) would have been double-sided, so there was plenty of light for the weavers. Many such weavers were also part-time agricultural labourers and farmers. They’d perfected a work-life balance within their control (if fragile and unpredictable).

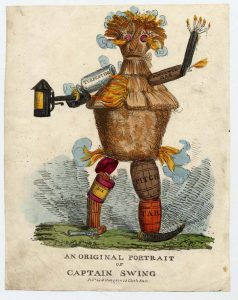

So little wonder that these labourers revolted. They were moved into factories – albeit with the same machinery – but now the machines were centrally powered and centrally controlled. Certain characters became figureheads for these new “employees”. “Captain Swing” was a penname for disgruntled agricultural workers who could see they were being replaced by new machines. But the Luddites (legendary smashers of machinery) were different. Most likely, they were really protesting about lack of control over their lives, and low wages.

The sharing gig economy – more control or less?

So, the gig economy, allowing us to turn spare time and assets into extra money, is a liberating concept – right? Possibly wrong, or at least misunderstood. Many entrepreneurial types take advantage of those most destabilised by the gig economy. I recently spied a collection of about 20 Toyota Priuses in various states of disrepair. It turned out they were all owned by the same guy. He rented them to drivers without cars, but with a need to work for Uber. These battered Priuses were awaiting repair after a heavy weekend.

How can workers be protected in the gig economy, and – like the Luddites – try to regain some control over their working lives? Much as with other revolutions: decent regulation and sticking together. We are seeing signs of this emerging. Workforces are us, not just a means of production, achieved at the lowest cost. As Henry Ford said, he wanted to build cars his workers could afford. A number of recent reports* suggest that as much as 50% of our work activities could be automated using current technology. Does this provide new opportunities or new threats?

There’s a disconnect here. Technological advances could improve our lives by improving our efficiency. In that process of improving our lives, we could render ourselves obsolete – not an improvement. So what are we forgetting? What are we bringing to our work that cannot be mechanised? Emotional connection, empathy, relationship. For a machine, relationships are merely data exchanges.

What about Artificial Intelligence?

Is it the golden solution to a life of leisure, or just further loss of control? Is it a saviour or a sinner? Is it with us or against us?

Perhaps your digital assistant can answer requests by searching its database. It can find you a restaurant from a list of local eateries. Yet, it can’t give you an emotional reaction to the taste of an orange. Being in the Internet of things is not the same as

People, are uniquely self-aware and have empathy and mastery of the gift of non-verbal communications. Let’s champion that. Let’s be people first, workers second, and concentrate on creating relationships.

*For example, one such piece from McKinsey Global Institute

Photo by Chris Barbalis on Unsplash